Being a part of a Macedonian home in the Western world is interesting. You have a lot of things to learn, a lot of rules to follow, and a lot of cooking and cleaning to do. These are the circumstances most diaspora members experience in the Macedonian household.

Thankfully, when it comes to keeping Macedonian culture in this household, parents typically push their children to learn how to speak both Macedonian and another language. In my case, like many others, I learned to speak Macedonian first, but then I stopped because I had to learn English for school. I later learned to speak it thoroughly when I was 7. Having children go through this means that the Macedonian culture will still be able to live on in other places. Unfortunately, in many instances, the culture has had to be put on the back-burner due to the immediate need of a family to assimilate and acclimate to a new location.

Typical Macedonian households, aside from valuing Macedonia’s culture and language, also value education. Parents usually hold their struggle to get here over their children to ensure they work hard because they “came here so you could get a better education and future”—meaning excellent grades must be maintained. This staple argument rebuttal is used to remind children where they came from and how to do something to show that there is a higher purpose to the sacrifices that have been made for them. I would be lying if I didn’t say that this mean getting almost straight A’s for as long as I could remember.

Not only does being in a Macedonian household change one’s habits, it also changes their taste buds. Being in a common Macedonian household means a feast of traditional Macedonian dishes is guaranteed– even for the smallest of gatherings. Whether that is for coffee or for a slava, parents and grandparents try to teach the youth as many recipes as they can to ensure that when they are off on their own one day, they can learn to make these for their own children, and try to keep their Macedonian culture alive. Don’t get me wrong- I could go for a typical Western meal any day, but burek, gravče and sirenje will always have a special place in my heart.

The Macedonian parenting style in Western culture is very hard to find a balance in. For instance, you might drink your first glass of rakija before you enter high school, but might not be able to go out past 10 pm unless you’re with Macedonians. Unfortunately, having this diaspora lifestyle means that your social life is barely existent unless you’re with Macedonians. For instance, if you had to go to dinner with Rachel from school, you wouldn’t be allowed. However if you were going to a party with Bojana, they wouldn’t care as much- after all, naši sme right?

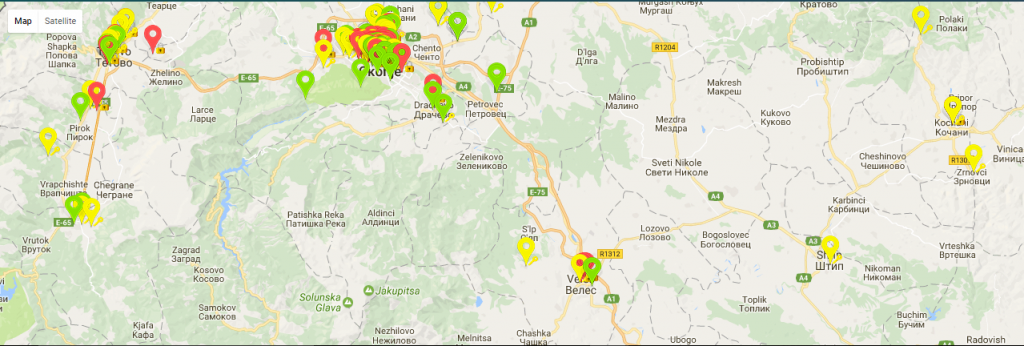

All of these little lessons taught from Macedonian households that are still adapting to a new society teach great skills of independence, hospitality and heritage. Although unconventional to onlookers, new generations of Macedonians are going to go far with what they have obtained in their household. However, in all of these a common thread of one lesson can be learned, which is to raise Macedonian kids to be proud of who they are. It is the best way for us to help our homeland, by raising Macedonians invested in helping our ancestral land and being able to make changes.

—

The views of the author may not necessarily reflect the views of the United Macedonian Diaspora and Generation M.